The Cloud Native Citizen: A Pattern Language for Kubernetes

- Kamran Biglari

- Kubernetes , Cloud Native , DevOps

- 15 Feb, 2026

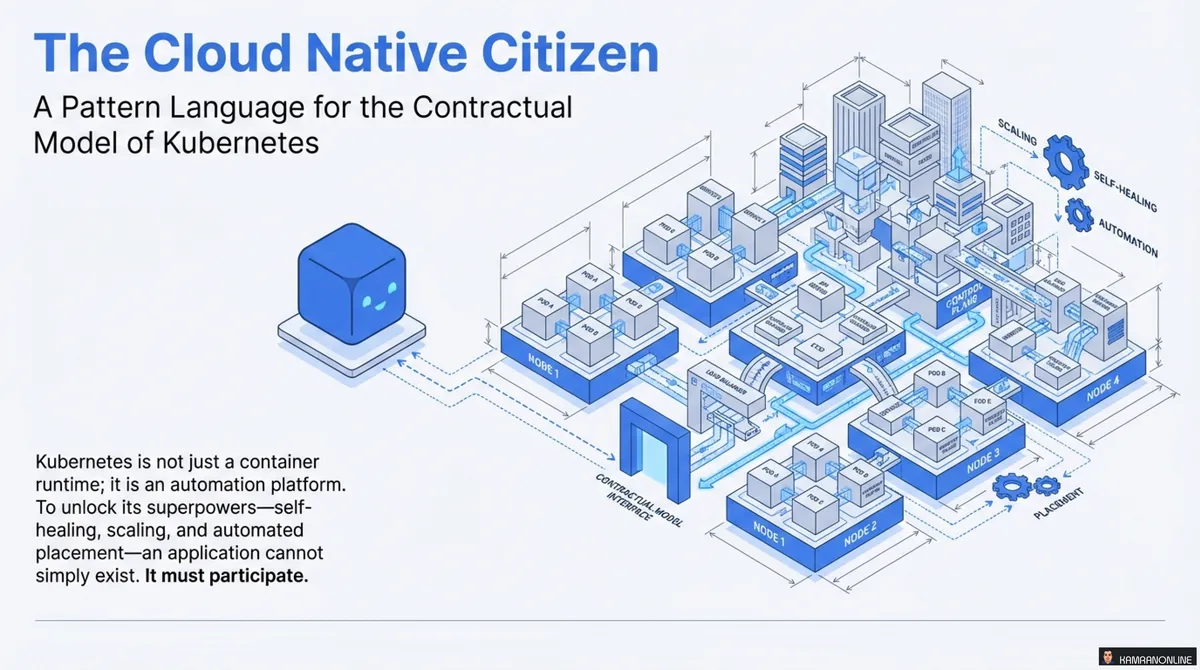

Just putting an application into a container doesn’t automatically make it cloud native. To truly leverage the power of platforms like Kubernetes, our applications need to adhere to specific contracts and principles to become “good cloud native citizens.”

Kubernetes is not just a container runtime; it’s an automation platform. To unlock its superpowers—self-healing, scaling, and automated deployments—your applications can’t simply exist. They must participate.

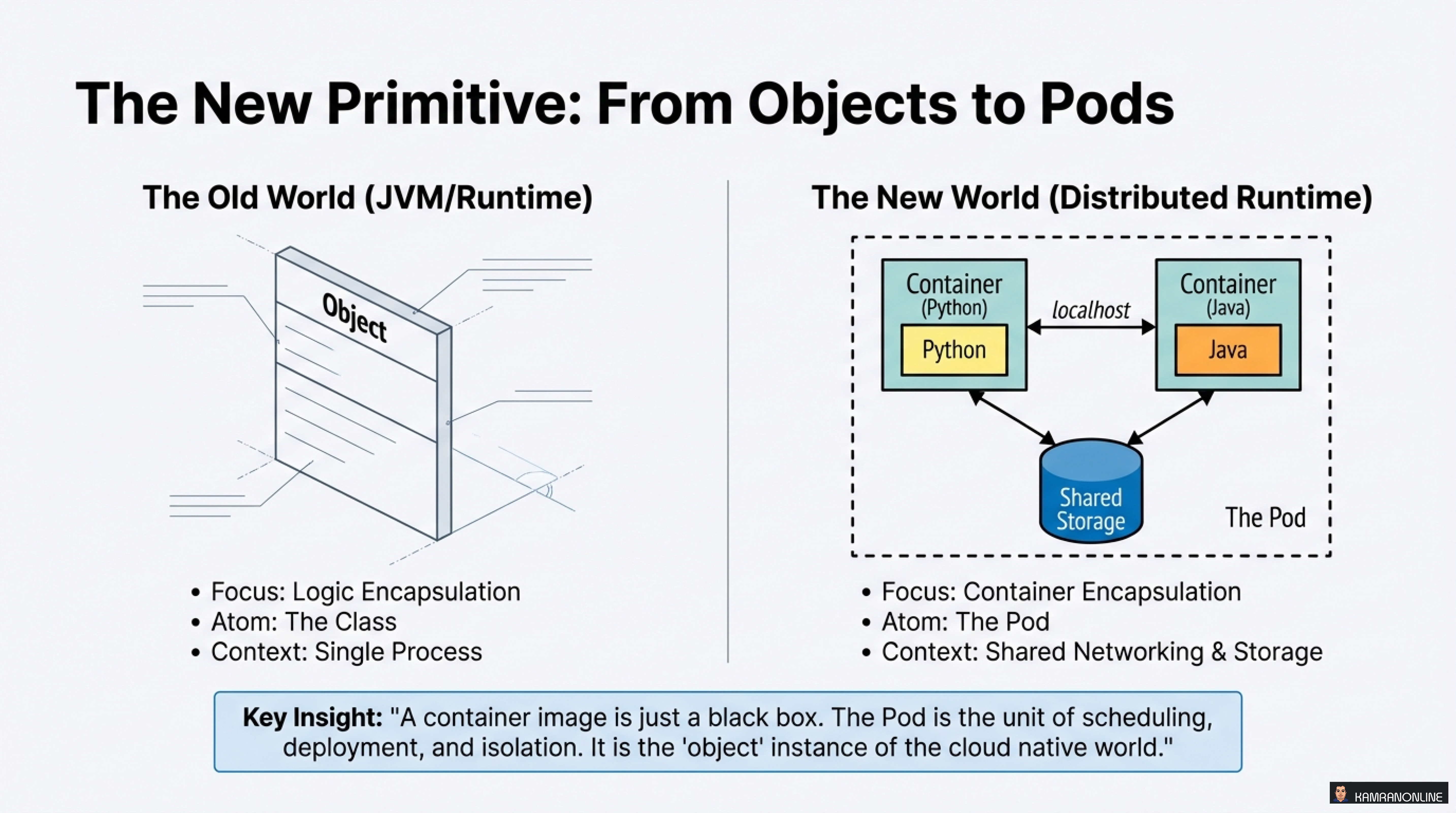

The Paradigm Shift: From Objects to Pods

In traditional application development, we focused on objects as the fundamental building blocks—classes encapsulating logic within a single process. The cloud native world introduces a new primitive: the Pod.

Key Insight

“A container image is just a black box. The Pod is the unit of scheduling, deployment, and isolation. It is the ‘object’ instance of the cloud native world.”

While the old world focused on logic encapsulation within a single runtime, the new distributed runtime focuses on container encapsulation with shared networking and storage. The Pod becomes the atomic unit that Kubernetes orchestrates.

The Four Contracts of Citizenship

To live harmoniously in the Kubernetes cluster, your application must sign four specific contracts with the platform:

- The Contract of Consumption - Declaring what resources are needed (Predictable Demands)

- The Contract of Communication - Telling the platform how you feel (Health Probes & Lifecycle)

- The Contract of Location - Defining where you belong (Automated Placement)

- The Contract of Evolution - Defining how you change (Declarative Deployment)

Let’s dive deep into each contract.

Contract #1: The Contract of Consumption

Understanding Resource Profiles

Not all resources are created equal. Kubernetes distinguishes between two types:

Compressible Resources (CPU)

- Nature: Can be throttled

- Starvation: Performance degrades, but process lives

- Mechanism: CPU Shares / Quotas

Incompressible Resources (Memory)

- Nature: Cannot be throttled

- Starvation: The platform kills the process (OOMKilled)

- Mechanism: Bytes

The Critical Principle

“In an environment with shared resources… the only way to ensure a successful coexistence is to know the demands of every process in advance.”

This is why setting resource requests and limits isn’t just configuration—it’s a matter of survival.

The Quality of Service (QoS) Pyramid

Kubernetes assigns every Pod to one of three QoS classes based on resource requests and limits:

Guaranteed (Requests = Limits)

- The first-class citizen

- Last to be killed under resource pressure

- Highest survival probability

Burstable (Requests < Limits)

- Safe within requests

- Throttled or killed if exceeding requests under pressure

- Medium survival probability

Best-Effort (No Requests / No Limits)

- The scavenger

- First to be killed to free up resources

- Lowest survival probability

Key Takeaway: The resource fields in your YAML aren’t just settings; they determine your application’s survival probability.

The Goldilocks Rules: Getting Resources Just Right

After managing hundreds of Kubernetes workloads, I’ve found these rules to be invaluable:

Rule 1: Memory - Always Set Requests Equal to Limits

Why? To achieve “Guaranteed” QoS and minimize the surprise of OOM (Out of Memory) evictions.

resources:

requests:

memory: "512Mi"

limits:

memory: "512Mi" # Same as requestsThis prevents your application from being killed unexpectedly and ensures predictable behavior.

Rule 2: CPU - Set Requests, but Do NOT Set Limits

Why? CPU is compressible. Setting a limit will artificially throttle your app even if the node is idle. Let the app use spare cycles; the kernel will throttle it automatically based on Requests if the node gets busy.

resources:

requests:

cpu: "500m"

# No limits - use spare cycles when availableCapacity Planning Best Practice

Use the Vertical Pod Autoscaler (VPA) to monitor consumption over time and recommend the right numbers. Don’t guess—measure!

Contract #2: The Contract of Communication

Your application must tell Kubernetes how it’s feeling. This is done through health probes and lifecycle hooks.

The Three Types of Probes

1. Liveness Probe (The Heartbeat)

- Question: Are you deadlocked?

- Action: Restart the container

- Use Case: Recovering from infinite loops, frozen states

2. Readiness Probe (The Traffic Light)

- Question: Are you overwhelmed?

- Action: Cut network traffic (remove from Service endpoints)

- Use Case: Waiting for database, warming caches, handling load spikes

3. Startup Probe (The Awakening)

- Question: Are you awake yet?

- Action: Pauses other probes until this passes

- Use Case: Slow-starting applications, preventing premature liveness failures

Speaking the Language: Probe Configuration

Here’s a practical example showing proper probe configuration:

livenessProbe:

httpGet:

path: /healthz

port: 8080

initialDelaySeconds: 30 # Give it time to boot

periodSeconds: 10 # Don't nag too often

readinessProbe:

exec:

command: ['stat', '/tmp/ready'] # Check for file existenceCritical Note: Different mechanisms for different needs. Liveness prevents “death loops” where K8s kills an app before it finishes booting. Use initialDelaySeconds wisely!

The Art of Dying Well: Managed Lifecycle

A good cloud native citizen doesn’t just run well—it shuts down gracefully.

The Termination Sequence

- Termination Event triggered (scale down, rolling update, etc.)

- PreStop Hook executes

- Blocking call for cleanup tasks

- Close connections, finish processing

- SIGTERM sent to the container

- The gentle poke: “Stop accepting new requests”

- Grace Period (default 30s)

terminationGracePeriodSeconds

- SIGKILL - The hard stop

- Process forcefully removed

The Golden Rule

“To be a good citizen, you must clean up after yourself before the lights go out.”

Implement proper signal handling in your application to:

- Drain existing connections

- Complete in-flight requests

- Save state if necessary

- Release resources cleanly

Contract #3: The Contract of Location

Where should your Pod run? Kubernetes uses a sophisticated scheduling funnel to make this decision.

The Two-Stage Scheduling Process

Stage 1: Filtering (Predicates)

- Which nodes are impossible?

- Checks: Resources, Ports, Taints, Node Selectors

Stage 2: Scoring (Priorities)

- Which node is the BEST fit?

- Considers: Spreading, Packing, Image Locality

Influencing the Decision: Attraction and Repulsion

Attraction (Affinity) - “I want to be here”

- Node Affinity: Run on nodes with SSDs or GPUs

- Pod Affinity: Run on the same node as my Cache (Speed)

Repulsion (Taints & Tolerations) - “Keep out”

- Taints: Applied to a Node (e.g., “Reserved for GPU”)

- Tolerations: Applied to a Pod - A ‘key card’ allowing entry to a tainted node

Key Distinction: Affinity is about selection (Opt-in). Taints are about exclusion (Opt-out).

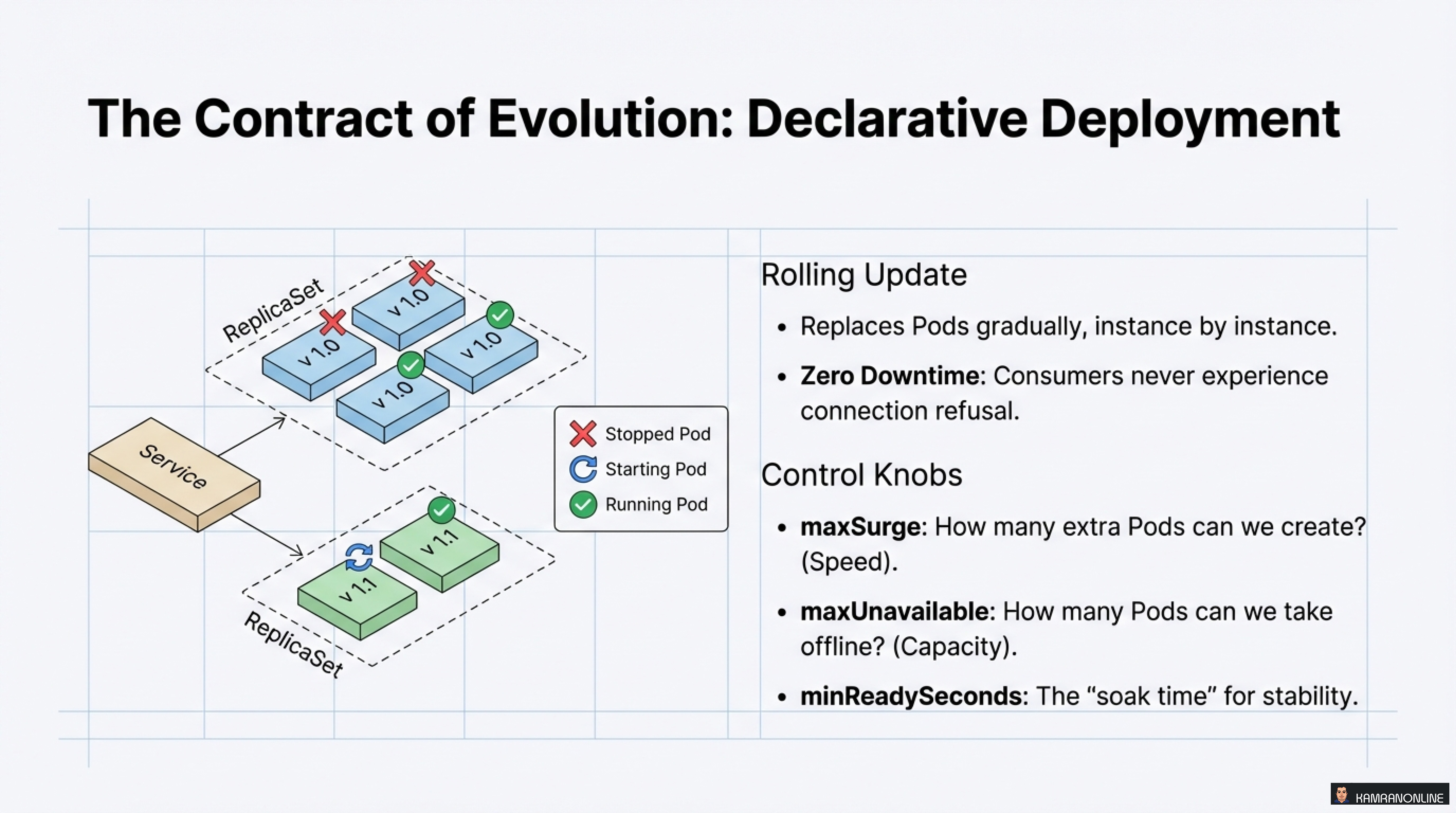

Contract #4: The Contract of Evolution

How does your application change over time? In the cloud native world, we use declarative deployment strategies.

Rolling Update: The Default Strategy

Kubernetes replaces Pods gradually, instance by instance:

Benefits:

- Zero Downtime - Consumers never experience connection refusal

- Controlled rollout - Problems affect limited scope

Control Knobs:

strategy:

type: RollingUpdate

rollingUpdate:

maxSurge: 1 # How many extra Pods can we create? (Speed)

maxUnavailable: 0 # How many Pods can we take offline? (Capacity)

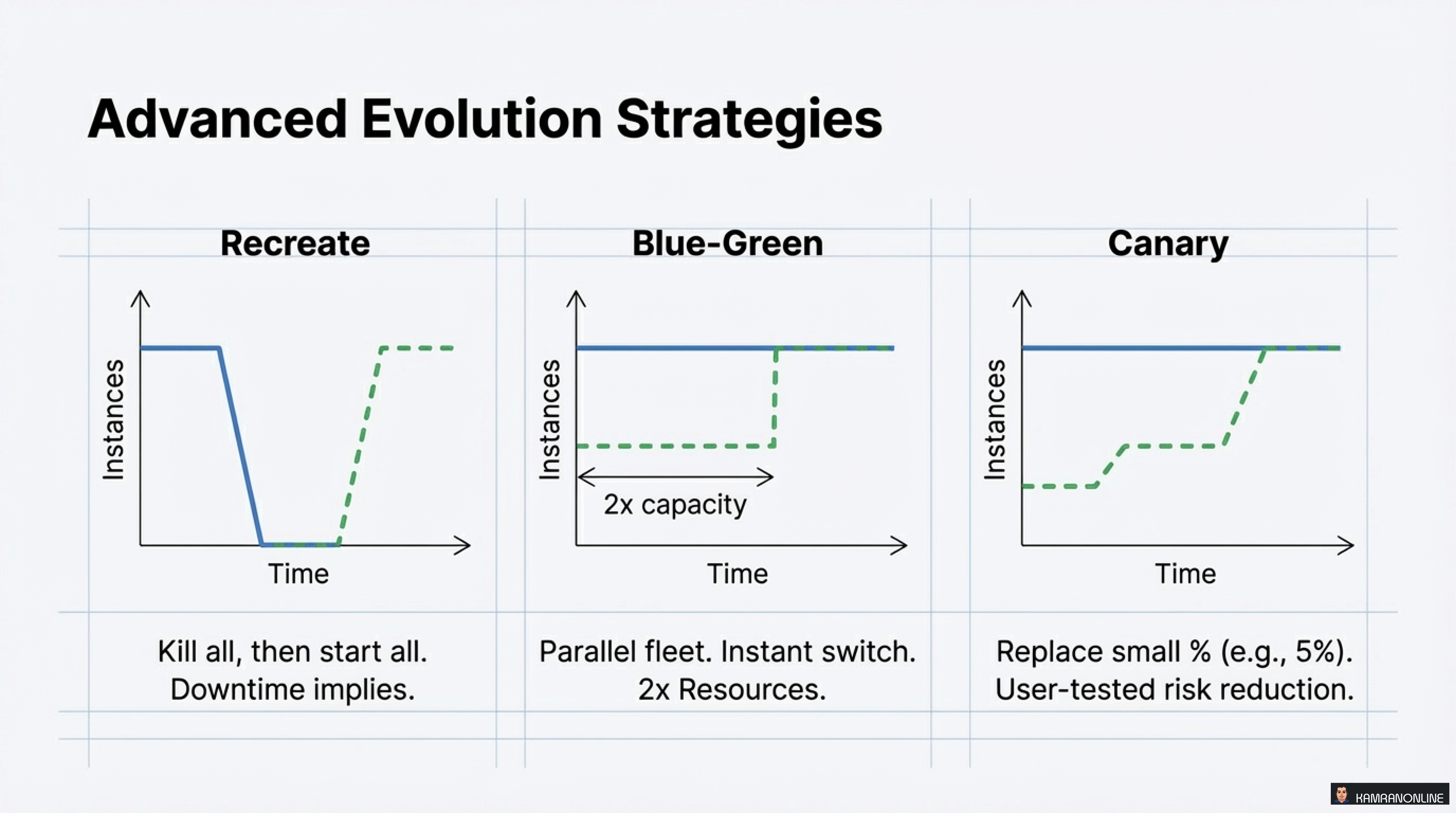

minReadySeconds: 10 # The "soak time" for stabilityAdvanced Evolution Strategies

1. Recreate

- Kill all, then start all

- Downtime implied

- Use case: Dev environments, schema migrations

2. Blue-Green

- Parallel fleet, instant switch

- 2x Resources required

- Use case: High-stakes deployments, instant rollback capability

3. Canary

- Replace small % (e.g., 5%)

- User-tested risk reduction

- Use case: Production deployments with gradual confidence building

Each strategy has its place depending on your risk tolerance, resource availability, and business requirements.

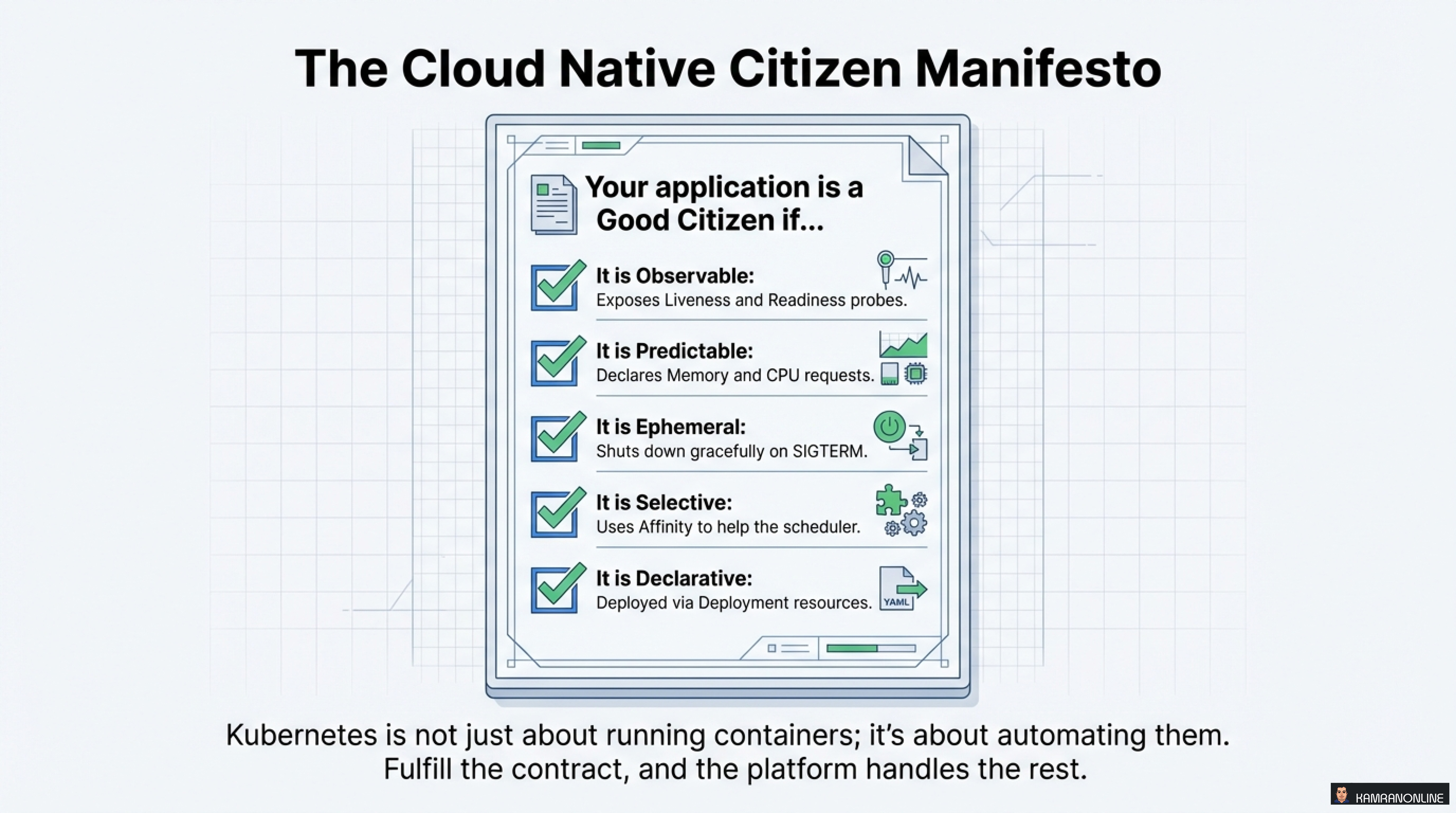

The Cloud Native Citizen Manifesto

Your application is a Good Citizen if it is:

✅ Observable

Exposes Liveness and Readiness probes so Kubernetes knows your state

✅ Predictable

Declares Memory and CPU requests so the scheduler can make informed decisions

✅ Ephemeral

Shuts down gracefully on SIGTERM, cleaning up resources properly

✅ Selective

Uses Affinity to help the scheduler place you optimally

✅ Declarative

Deployed via Deployment resources (not imperative kubectl run commands)

Conclusion: Kubernetes is About Automation, Not Just Containers

The key insight that ties all of this together:

Kubernetes is not just about running containers; it’s about automating them. Fulfill the contract, and the platform handles the rest.

When you properly implement these four contracts—Consumption, Communication, Location, and Evolution—you’re not just deploying an application. You’re creating a self-managing, resilient, automated system that can:

- Self-heal when things go wrong

- Auto-scale based on demand

- Deploy with zero downtime

- Optimize resource usage across your cluster

The journey from “containerized” to “cloud native” requires understanding and implementing these patterns. Start with one contract at a time, measure the results, and iterate.

Your applications will thank you. Your operations team will thank you. And most importantly, your users will benefit from a more reliable, scalable system.

Key Takeaways

- The Pod is the new primitive - Think in terms of Pods, not just containers

- Resource requests determine survival - Use the Goldilocks Rules for memory and CPU

- Health probes enable automation - Implement all three types appropriately

- Graceful shutdown matters - Handle SIGTERM and use PreStop hooks

- Influence scheduling thoughtfully - Use affinity and taints when needed

- Declarative deployments win - Rolling updates with proper configuration provide zero-downtime changes

Becoming a good cloud native citizen isn’t about adding more complexity—it’s about understanding the platform’s contract and designing applications that work with Kubernetes, not against it.

What patterns have you found most valuable when running applications on Kubernetes? Share your experiences in the comments or reach out to me on LinkedIn.